| Thoth | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Egyptian: Djehuty | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Period of worship |

Predynastic – Roman Period | ||||||||||

| Cult center | Hermopolis | ||||||||||

| Titles | "Lord of Ma'at" "Scribe of Ma'at in the Company of the Gods" "Lord of Divine Words" "Judge of the Two Combatant Gods" | ||||||||||

| Symbol(s) | Ibis, moon disk, papyrus scroll, reed pens, writing palette, stylus, baboon, scales | ||||||||||

| Association | Knowledge, writing, moon | ||||||||||

| Appearance | Therianthrope, ibis, baboon | ||||||||||

| Greek equivalent(s) |

Hermes | ||||||||||

| Egyptian equivalent(s) |

Iah | ||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Ma'at, Seshat, Nehmetawy | ||||||||||

| Issue | Seshat | ||||||||||

Thoth, a Greek name derived from the Egyptian *ḏiḥautī (djih-how-tee) (written by Egyptians as ḏḥwty) was considered one of the most important deities of the Egyptian pantheon. His feminine counterpart was Ma'at.[1] His chief shrine was at Khemennu, where he was the head of the local company of gods, later renamed Hermopolis by the Greeks (in reference to him through the Greeks' interpretation that he was the same as Hermes) and Eshmûnên by the Arabs. He also had shrines in Abydos, Hesert, Urit, Per-Ab, Rekhui, Ta-ur, Sep, Hat, Pselket, Talmsis, Antcha-Mutet, Bah, Amen-heri-ab, and Ta-kens.[2]

He was considered the heart and tongue of Ra as well as the means by which Ra's will was translated into speech.[3] He has also been likened to the Logos of Plato[4] and the mind of God.[5] In Egyptian mythology, he has played many vital and prominent roles, including being one of the two gods, the other being his feminine counterpart Ma'at, who stood on either side of Ra's boat.[6] He has further been involved in arbitration[7], magic, writing, science[8], and the judging of the dead.[9]

Name[]

Etymology[]

According to Theodor Hopfner[10], Thoth's Egyptian name written as ḏḥwty originated from ḏḥw, claimed to be the oldest known name for the ibis although normally written as hbj. The addition of -ty denotes that he possessed the attributes of the ibis.[11] Hence his name means "He who is like the ibis".

The Egyptian pronunciation of ḏḥwty is not fully known, but may be reconstructed as *ḏiḥautī, based on the Ancient Greek borrowing Θωθ Thōth or Theut and the fact that it evolved into Sahidic Coptic variously as Thoout, Thōth, Thoot, Thaut as well as Bohairic Coptic Thōout. The final -y may even have been pronounced as a consonant, not a vowel.[12] However, many write "Djehuty", inserting the letter 'e' automatically between consonants in Egyptian words, and writing 'w' as 'u', as a convention of convenience for English speakers, not the transliteration employed by Egyptologists.[13]

Alternate names[]

| Alternate names for Thoth in Hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A

Sheps, lord of Khemennu

Asten

Khenti (not found)

Mehi

Hab

Aan

A'ah-Djehuty

|

Djehuty is sometimes alternatively rendered as Tahuti, Tehuti, Zehuti, Techu, or Tetu. Thoth (also Thot or Thout) is the Greek version derived from the letters ḏḥwty.

Not counting differences in spelling, Thoth had more than one name, like other gods and goddesses. Similarly, each Pharaoh, considered a god himself, had five different names used in public.[15] Among his alternate names are A, Sheps, Lord of Khemennu, Asten, Khenti, Mehi, Hab, and A'an.[16] In addition, Thoth was also known by specific aspects of himself, for instance the moon god A'ah-Djehuty, representing the moon for the entire month.[17] Further, the Greeks related Thoth to their god Hermes due to his similar attributes and functions.[18] One of Thoth 's titles, "Three times great, great" was translated to the Greek τρισμεγιστος (Trismegistos) making Hermes Trismegistus.[19]

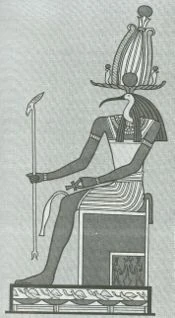

Depictions[]

Thoth has been depicted in many ways depending on the era and aspect the artist wished to convey. Usually, he is depected in human form with the head of an ibis.[20] In this form, he can be represented as the reckoner of times and seasons by a lunar disk sitting in a crescent moon being placed atop his head. When depicted as a form of Shu or Ankher, he will wear the respective god's headdress. He also is sometimes seen wearing the atef crown and the United Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.[21]

When not depicted in this common form, he sometimes takes the form of the ibis directly.[22] He also appears as an ape when he is A'an, the god of equilibrium.[23] In the form of A'ah-Djehuty he took a more human looking form.[24]

These forms are all symbolic and are metaphors for Thoth's attributes. The Egyptians did not believe these gods actually looked like humans with animal heads. For example, Thoth's counterpart Ma'at is often depicted with an ostrich feather for a head.[25]

Attributes[]

Egyptologists disagree on Thoth's nature depending upon their view of the Egyptian pantheon. Most egyptologists today side with Flinders Petrie that Egyptian religion was strictly polytheistic, in which Thoth would be a separate god. His contemporary adversary, E. A. Wallis Budge, however, thought Egyptian religion to be primarily monotheistic[26] where all the gods and goddesses were aspects of the God Ra, similar to the Trinity in Christianity and Devas in Hinduism.[27] In this view, Thoth would be the aspect of Ra which the Egyptian mind would relate to the heart and tongue.

His roles in Egyptian mythology were many. Thoth served as a mediating power, especially between good and evil, making sure neither had a decisive victory over the other.[28] He also served as scribe of the gods[29], credited with the invention of writing and alphabets (ie. hieroglyphs) themselves.[30] In the underworld, Duat, he appeared as an ape, A'an, the god of equilibrium, who reported when the scales weighing the deceased's heart against the feather, representing the principle of Ma'at, was exactly even.[31]

The ancient Egyptians regarded Thoth as One, self-begotten, and self-produced.[32] He was the master of both physical and moral (ie. Divine) law,[33] making proper use of Ma'at.[34] He is credited with making the calculations for the establishment of the heavens, stars, Earth[35], and everything in them.[36] Compare this to how his feminine counterpart, Ma'at was the force which maintained the Universe.[37] He is said to direct the motions of the heavenly bodies. Without his words, the Egyptians believed, the gods would not exist.[38] His power was almost unlimited in the Underworld and rivalled that of Ra and Osiris.[39]

The Egyptians credited him as the author of all works of science, religion, philosophy, and magic.[40] The Greeks further declared him the inventor of astronomy, astrology, the science of numbers, mathematics, geometry, land surveying, medicine, botany, theology, civilized government, the alphabet, reading, writing, and orator. They further claimed he was the true author of every work of every branch of knowledge, human and divine.[41]

Mythology[]

Thoth has played a prominent role in many of the Egyptian myths. Displaying his role as arbitrator, he had overseen the three epic battles between good and evil. All three battles are fundamentally the same and belong to different periods. The first battle took place between Ra and Apep, the second between Heru-Bekhutet and Set, and the third between Horus, the son of Osiris, and Set. In each instance, the former god represented good while the latter represented evil. If one god was seriously injured, Thoth would heal them to prevent either from overtaking the other.

Thoth was also prominent in the Osiris myth, being of great aid to Isis. After Isis gathered together the pieces of Osiris' dismembered body, he gave her the words to resurrect him so she could be impregnated and bring forth Horus, named for his uncle. When Horus was slain, he gave the formulae to resurrect him as well. Similar to God speaking the words to create the heavens and Earth in Judeo-Christian mythology, Thoth, being the god who always speaks the words that fulfill the wishes of Ra, spoke the words that created the heavens and Earth in Egyptian mythology.

Mythology also accredits him with the creation of the 365 day calendar. Originally, according to the myth, the year was only 360 days long and Nut with sterility during these days, unable to bear children. Thoth gambled with Khonsu, the moon, for 1/72nd of its light (360/72 = 5), or 5 days, and won. During these 5 days, she gave birth to Kheru-ur (Horus the Elder, Face of Heaven), Osiris, Set, Isis, and Nepthys.

In the Ogdoad cosmogony myth, Thoth gave birth to Ra, Atum, Nefertum, and Khepri by laying an egg while in the form of an ibis, or later as a goose laying a golden egg.

History[]

Thoth, sitting on his throne.

He was originally the deification of the moon in the Ogdoad belief system. Initially, in that system, the moon had been seen to be the eye of Horus, the sky god, which had been semi-blinded (thus darker) in a fight against Set, the other eye being the sun. However, over time it began to be considered separately, becoming a lunar deity in its own right, and was said to have been another son of Ra. As the crescent moon strongly resembles the curved beak of the ibis, this separate deity was named Djehuty (i.e. Thoth), meaning ibis.

Thoth became associated with the Moon, due to the Ancient Egyptians observation that Baboons (sacred to Thoth) 'sang' to the moon at night.

The Moon not only provides light at night, allowing the time to still be measured without the sun, but its phases and prominence gave it a significant importance in early astrology/astronomy. The cycles of the moon also organized much of Egyptian society's civil, and religious, rituals, and events. Consequently, Thoth gradually became seen as a god of wisdom, magic, and the measurement, and regulation, of events, and of time. He was thus said to be the secretary and counsellor of Ra, and with Ma'at (truth/order) stood next to Ra on the nightly voyage across the sky, Ra being a sun god.

Thoth became credited by the ancient Egyptians as the inventor of writing, and was also considered to have been the scribe of the underworld, and the moon became occasionally considered a separate entity, now that Thoth had less association with it, and more with wisdom. For this reason Thoth was universally worshipped by ancient Egyptian Scribes.

In art, Thoth was usually depicted with the head of an ibis, deriving from his name, and the curve of the ibis' beak, which resembles the crescent moon. Sometimes, he was depicted as a baboon holding up a crescent moon, as the baboon was seen as a nocturnal, and intelligent, creature. The association with baboons led to him occasionally being said to have as a consort Astennu, one of the (male) baboons at the place of judgement in the underworld, and on other occasions, Astennu was said to be Thoth himself.

During the late period of Egyptian histor] a cult of Thoth gained prominence, due to its main centre, Khnum (Hermopolis Magna), also becoming the capital, and millions of dead ibis were mummified and buried in his honour. The rise of his cult also led to his cult seeking to adjust mythology to give Thoth a greater role.

Thoth was inserted in many tales as the wise counsel and persuader, and his association with learning, and measurement, led him to be connected with Seshat, the earlier deification of wisdom, who was said to be his daughter, or variably his wife. Thoth's qualities also led to him being identified by the Greeks with their closest matching god - Hermes, with whom Thoth was eventually combined, as Hermes Trismegistus, also leading to the Greeks naming Thoth's cult centre as Hermopolis, meaning city of Hermes.

It is also viewed that Thoth was the God of Scribe and not a messenger. Anubis was viewed as the messenger of the gods, as he travelled in and out of the Underworld, to the presence of the gods, and to humans, as well. Some call this fusion Hermanubis. It is in more favor that Thoth was a record keeper, and not the messenger.

There is also an Egyptian Pharaoh of the Sixteenth Dynasty named Djehuty (Thoth) after him, and who reigned for three years.

Titles[]

| Titles belonging to Thoth in Hieroglyphs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scribe of Ma'at in the Company of the Gods

Lord of Ma'at

Lord of Divine Words

Judge of the Two Combatant Gods

Judge of the Rekhekhui, the Pacifier of the Gods, who Dwelleth in Unnu, the Great God in the Temple of Abtiti

Twice Great

Thrice Great

Three Times Great, Great

|

Thoth, like many Egyptian gods and nobility, held many titles. Among these were "Scribe of Ma'at in the Company of the Gods," "Lord of Ma'at," "Lord of Divine Words," "Judge of the Two Combatant Gods,"[43] "Judge of the Rekhekhui, the pacifier of the Gods, who Dwelleth in Unnu, the Great God in the Temple of Abtiti,"[44] "Twice Great," "Thrice Great,"[45] " and "Three Times Great, Great."[46]

Thoth in more recent times[]

One of the most popular and cited works on the Tarot was connected to this deity. Written by the occultist Aleister Crowley, The Book of Thoth is a philosophical text on the usage of Tarot and, most notably, Crowley's own created Tarot Deck, the Thoth Tarot which he also referred to as The Book of Thoth, where the name is taken from a "non-existent" (translations from papyrus of an actual book of thoth DO exist, titled 'The Ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth' by Jasnow and Zauzich) book in Egyptian mythology, believed to contain ancient knowledge originally brought to man by this deity. Crowley commissioned Lady Frieda Harris to assist him in painting the Thoth Deck.

A text entitled The Emerald Tablets of Thoth-The-Atlantean has been claimed to have been translated by a man named Doreal. The introduction claims them to be written by an Atlantean Priest-King named Thoth, who settled a colony in Egypt after Atlantis sunk. Doreal further claims the texts are 36,000 years old.[47] Regardless of the authenticity of the text, it contains much Hermetic and Egyptian symbolism that Doreal misses.

Thoth/Djehuty in pop culture[]

- The Orbital Frame Jehuty, from the game, Zone of the Enders (published by Konami) is based on Thoth/Djehuty.

- Using the name 'Mister Ibis', Thoth works as a mortician alongside Anubis (as 'Mister Jacquel') in Cairo, Illinois, in Neil Gaiman's American Gods.

- The Ring of Thoth (aka: The Mummy) was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle for The Cornhill Magazine published Jan 1890.[1]

- Thoth was a minor Goa'uld scientist serving Anubis in the Kull Warrior R&D on the planet Tartarus. Thoth was killed by Samantha Carter. (Season 7 Stargate SG-1 episode "Evolution part II")

- Thoth is also a Carnival Krewe in New Orleans, Louisiana, which parades on the Sunday before Mardi Gras. The Krewe features a float decorated with a large depiction of the ancient deity.

- Djehuty is the name of a three-dimensional radiative hydrodynamical code for modelling stars at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.[2]

- He is also the administrator of the Library where superhero/librarian Rex works, in the comic Rex Libris by James Turner

- In Age of Mythology, Thoth can be worshipped. He grants his followers Phoenixes, War Turtles and Meteors.

- Thoth appears in the OKEY-DOKEY comic book series as the Non-Local Prometheus.

- Thoth was the name of an Artificial Intelligence in the Marathon Trilogy, created by the S'pht on their homeworld, Lh'owon.

- Thoth, as a person's name has appeared at least twice in the late twentieth century.

- S. K. Thoth is the name of a street performer, who was born in 1954, in Queens, New York, U.S.A. Sarah Kernochan directed a film about him in 2002, which won an Academy Award, in the same year.

- Thoth Harris (born, in 1972, in North Vancouver, B.C. Canada), is the name of a writer and spoken word performer who hosted spoken word cabarets in Montreal, Quebec, Canada from 1998 - 2002. He now lives in Fongyuan, Taiwan as a teacher, and writes a blog entitled The Montreal Writers' Storm Sewer.[3]

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 400)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 415)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 400)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 403)

- ↑ Hopfner, Theodor, b. 1886. Der tierkult der alten Agypter nach den griechisch-romischen berichten und den wichtigeren denkmalern. Wien, In kommission bei A. Holder, 1913. Call#= 060 VPD v.57

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402)

- ↑ Information taken from phonetic symbols for Djehuty, and explanations on how to pronounce based upon modern rules, revealed in (Collier and Manley pp. 2-4, 161)

- ↑ (Collier and Manley p. 4)

- ↑ Hieroglyphs from (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 402-3)

- ↑ (Collier and Manley p. 20)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 402-3)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 412-3)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 402)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 415)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 plate between pp. 408-9)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 416)

- ↑ (Budge Egyptian Religion pp. 17-8)

- ↑ (Budge Egyptian Religion p. 29)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 408)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 407-8)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 408)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Hall The Hermetic Marriage p. 224)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ↑ Heiroglyphs verified in (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 401, 405, 415)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 415)

- ↑ (Doreal p. i)

Bibliography[]

- Bleeker, Claas Jouco. 1973. Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion. Studies in the History of Religions 26. Leiden: E. J. Brill

- Boylan, Patrick. 1922. Thot, the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt. London: Oxford University Press. (Reprinted Chicago: Ares Publishers inc., 1979)

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. Egyptian Religion. Kessinger Publishing, 1900.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The Gods of the Egyptians Volume 1 of 2. New York: Dover Publications, 1969 (original in 1904).

- Černý, Jaroslav. 1948. "Thoth as Creator of Languages." Journal of Egyptian Archæology 34:121–122.

- Collier, Mark and Manley, Bill. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Doreal. The Emerald Tablets of Thoth-The-Atlanean. Alexandrian Library Press, date undated.

- Fowden, Garth. 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Mind. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993). ISBN 0-691-02498-7

- Hall, Manly P. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. San Francisco: H.S. Crocker Company, 1928.