| Preceded by: Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten |

Pharaoh of Egypt 18th Dynasty |

Succeeded by: Ay | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tutankhamun | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atenistic: Tutankhaten Manetho: Rhathotis/Rathos Akkadian cuneiform: Nibḫurureya | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1332–1323 BC or 1322-1313 BC (9 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Praenomen |

The Lord of Manifestations is Re | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen |

The Image of Amun Lives, Ruler of Southern Heliopolis | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Strong Bull, Pleasing of Birth | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name |

Perfect of Laws, He who Pacifies the Two Lands | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus |

Elevated of Appearances, He who Satisfies the Gods | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | KV55 Mummy (Akhenaten or Smenkhkare) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | The Younger Lady | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort(s) | Ankhesenamun | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Two stillborn daughters | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1241 or 1231 BC, Amarna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1223 or 1213 BC (aged 18-19) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | KV62 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Nebkheperure Tutankhamun (ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-ỉmn, "The Image of Amun Lives"), commonly referred to as King Tut, was a Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom.

In historical terms, Tutankhamun is of only moderate significance, and most of his modern popularity stems from the fact that his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered almost completely intact. However, he is also significant as a figure who managed the beginning of the transition from the heretical Atenism of his predecessors Akhenaten and Smenkhkare back to the familiar Religion. As Tutankhamun began his reign at age 9, his vizier and eventual successor Ay was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun's reign. Nonetheless, Tutankhamun is, in modern times, the most famous of the Pharaohs, and the only one to have a nickname in popular culture ("King Tut"). The 1923 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun's nearly intact tomb (subsequently designated KV62) received worldwide press coverage and sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, of which Tutankhamun remains the popular face.

Tutankhamun's parentage is uncertain. An inscription calls him a king's son, but it is not clear which king was meant. Most scholars think that he was probably a son either of Amenhotep III (though probably not by his Great Royal Wife Tiye), or more likely a son of Amenhotep III's son Akhenaten around 1342 BC. However, Professor James Allen argues that Tutankhamun was more likely to be a son of the short-lived king Smenkhkare rather than Akhenaten. Allen argues that Akhenaten consciously chose a female co-regent named Neferneferuaten to succeed him rather than Tutankhamun which is unlikely if the latter was indeed his son.[1] Tutankhamun was married to Ankhesenpaaten (possibly his sister), and after the re-establishment of the traditional Egyptian religion the couple changed the –aten ending of their names to the –amun ending, becoming Ankhesenamun and Tutankhamun. They had two known children, both stillborn girls – their mummies were discovered in his tomb.

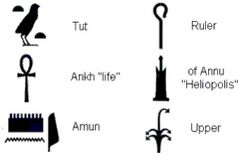

Name[]

Tutankhamun's nomen (left) or birth name and praenomen or throne name.

As a young prince living in Amarna, Tutankhamun was known as Tutankhaten. The original nomen, Tutankhaten, did not have a Nebty name or a Gold Falcon name associated with it as nothing has been found with the full five-name protocol. Tutankhaten was believed to mean "Living-image-of-Aten" as far back as 1877; however, not all Egyptologists agree with this interpretation. English Egyptologist Battiscombe Gunn believed that the older interpretation did not fit with Akhenaten's theology. Gunn believed that such an name would have been blasphemous. He saw tut as a verb and not a noun and gave his translation in 1926 as The-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing. Professor Gerhard Fecht also believed the word tut was a verb. He noted that Akhenaten used tit as a word for 'image', not tut. Fecht translated the verb tut as "To be perfect/complete". Using Aten as the subject, Professor Gerhard Fecht's full translation was "One-perfect-of-life-is-Aten". Two carved block fragments discovered in el-Ashmunein have a unique spelling of the first nomen written as Tutankhuaten; it uses ankh as a verb, which does support the older translation of Living-image-of-Aten.[2]

The name change to Tutankhamun came with the reinstallation of the traditional Ancient Egyptian religion and restoration of old monuments, damaged and/or abandoned during the previous Amarna Period. In its orthodox form Tutankhamun's entire royal titulary is known.

Tutankhamun is known as Rhathotis (Pαθωτις) in Josephus version of Manetho's Epitome. Upon coronation, Tutankhamun adopted the throne name (or prenomen) Nebkheperure (ancient Egyptian: nb-ḫpr.w-rꜥ, "The Lord of Manifestations is Re"). Amarna letter EA 9, is by many scholars believed to have been written to Tutankhamun instead of Akhenaten. If true, his throne name is written as Nibḫurureya in cuneiform. Tutankhamun is usually attested with the epithet Heqaiunushema (ancient Egyptian: ḥḳꜣ-ỉwnw-šmꜥ, "The Ruler of Southern Heliopolis") after his birth name (or nomen). His whole name is thus realised as Nebkheperure Tutankhamun-Heqaiunushema.

The Lord of Manifestations is Re |

| At Amarna | |||||||||||||||||||

The Image of the Aten Lives | |||||||||||||||||||

| After Amarna | |||||||||||||||||||

The Image of Amun Lives, Ruler of Southern Heliopolis |

Strong Bull, Pleasing of Birth |

Perfect of Laws, He who Pacifies the Two Lands |

Elevated of Appearances, He who Satisfies the Gods |

Family[]

- See also: 18th Dynasty Family Tree.

An inscription from Hermopolis Magna refers to "Tutankhuaten" as a "King's Son". However, Tutankhamun's parentage is uncertain — the leading theories are that he was a son of Akhenaten, Smenkhkare or even Amenhotep III. His mother had generally been proposed to be Nefertiti or Kiya. When Tutankhaten became king, he married Ankhesenpaaten, one of Akhenaten's daughters, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun.[3] They had two daughters, neither of whom survived infancy. They were both interred in their father's KV62 tomb within small coffins. While only an incomplete genetic profile was obtained from the two mummified foetuses, it was enough to confirm that Tutankhamun was their father.[4]

Parentage[]

In 2008, genetic analysis was carried out on the mummified remains of Tutankhamun and others thought or known to be New Kingdom royalty by a team from University of Cairo. The results indicated that his father was the mummy from tomb KV55, who is either Akhenaten or Smenkhkare depending on the accepted age for the mummy. The team reported it was over 99.99 percent certain that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[5] Tutankhamun's mother was the mummy from tomb KV35, known as the "Younger Lady", who was found to be a full sister of her husband.[4]

Dates and Length of Reign[]

Tutankhamun's highest attestation is his regnal Year 9, which appears on six wine dockets found in his KV62 tomb. He therefore probably died between the vintages of his Year 9 and Year 10. A Year 10 docket found on one of the wine jars from his tomb has been convincingly demonstrated to belong to Akhenaten's reign instead, while another of Year 31 belongs to Amenhotep III.[6] Tutankhamun's highest attestation (excluding wine dockets) occurs as Year 8 on two stelae (Liverpool, Institute of Archeology E90 and E583).[7]

Reign[]

During Tutankhamun's reign, Akhenaten's Amarna revolution (Atenism) began to be reversed. Akhenaten had attempted to supplant the existing priesthood and Gods with a god who was until then

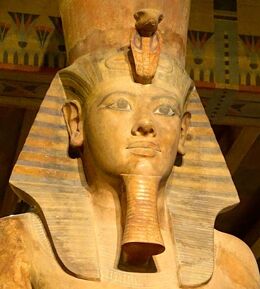

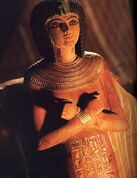

Tutankhamun's former home after he left Armana during the Armana Revolution, ending the chaos his father caused

considered minor, Aten. In Year 3 of Tutankhamun's reign (1331 BC), when he was still a boy of about 11 and probably under the influence of two older advisors (notably Akhenaten's vizier Ay), the ban on the old pantheon of Gods and their temples was lifted, the traditional privileges restored to their priesthoods, and the capital moved back to Thebes. The young pharaoh also adopted the name Tutankhamun, changing it from his birth name Tutankhaten. Because of his age at the time these decisions were made, it is generally thought that most if not all the responsibility for them falls on his vizier Ay and perhaps other advisors. Also, King Tutankhamun restored all the old gods and brought order to the chaos that his relative had caused. He built many temples devoted to the true sun god, Amun-Ra. It appears that on Tutankhamun's wooden box (pictured above) depicts him going to war against Hittites and Nubians suggesting that possibly that in the last few years of his reign that he went to war that possibly that he died going to war (as explained three sections below).

Events after his death[]

Tutankhamun Shabti

A now-famous letter to the Hittite king Suppiluliumas I from a widowed queen of Egypt, explaining her problems and asking for one of his sons as a husband, has been attributed to Ankhesenamun (among others). Suspicious of this good fortune, Suppiluliumas I first sent a messenger to make inquiries on the truth of the young queen's story. After reporting her plight back to Suppiluliumas I, he sent his son, Zannanza, accepting her offer. However, he got no further than the border before he died, perhaps murdered. If Ankhesenamun were the queen in question, and his death a murder, it was probably at the orders of Horemheb or Ay, who both had the opportunity and the motive to kill him.

Military Successes[]

Tutankhamun as Ruler of Nubia

Little was known about Tutankhamun when his tomb was discovered in 1922. He ruled sometime after the heretic

Tutankhamun's Dagger

pharaoh Akhenaten--who abandoned the traditional Egyptian pantheon headed by the god Amun in favor of Aten, a solar deity--and presumably died young after an insignificant reign. Since then, the "boy king" tag has colored our understanding of the young king. But new discoveries contradict that early assessment. Recent CT scanning of his mummy shows that Tut was no boy at death, but was a grown man by the

Tutankhamun Suppressing a Nubian Revolt

standards of the time and may have been 20 years old. And his 8- to 9-year reign toward the end of the 14th century B.C. was one of the greatest periods of restoration in the history of Egypt. Under Tut, the damage caused by Akhenaten's iconoclastic fury against the state god Amun, which tore the country's social, political, and economic fabric asunder, was repaired and Amun's cult restored.

The rich array of objects found in Tutankhamun's tomb speak to the opulence of the Egyptian court and the young king's pampered life. But other items, including numerous throwsticks (sort of non-returning boomerangs), spears, bows and arrows, and chariots--many inscribed with his name and clearly used--attest his athleticism and youthful energy. Today, new evidence of Tutankhamun's reign has emerged that shows he was much more active than was thought, and may have led military campaigns against the Syrians and Nubians before he died.

Cause of death[]

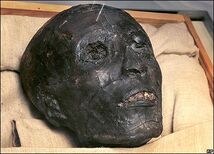

For a long time the cause of Tutankhamun's death was unknown, and was the root of much speculation. How old was the king when he died? Did he suffer from any physical abnormalities? Had he been murdered? Many of these questions were finally answered in early 2005 when the results of a set of CT scans on the

Tutankhamun's Mummy's Mask

mummy were released. The body was originally inspected by Howard Carter's team in the early 1920s, though they were primarily interested in recovering the jewellery and amulets from the body. To remove the objects from the body, which in many cases were stuck fast by the hardened embalming resins used, Carter's team cut up the mummy into various pieces: the arms and legs were detached, the torso cut in half and the head was severed. Hot knives were used to remove it from the golden mask to which it was cemented by resin. Since the body was placed back in its sarcophagus in 1926, the mummy has subsequently been X-rayed three times: first in 1968 by a group from the University of Liverpool, then in 1978 by a group from the University of Michigan and finally in 2005 a team of Egyptian scientists led by Secretary General of the

Tutankhamun's Sarcophagus

Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities Dr. Zahi Hawass conducted a CT scan on the mummy.

X-rays of his mummy, which were taken previously, in 1968, had revealed a dense spot at the lower back of the skull. This had been interpreted as a chronic subdural hematoma, which would have been caused by a blow. Such an injury could have been the result of an accident, but it had also been suggested that the young pharaoh was murdered. If this is the case, there are a number of theories as to who was responsible: one popular candidate was his immediate successor Ay (other candidates

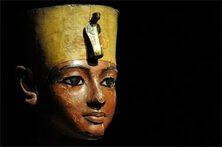

Tutankhamun wearing a Nemes crown, from a Canopic Jar

included his wife and chariot-driver). Interestingly, there are seemingly signs of calcification within the supposed injury, which if true meant Tutankhamun lived for a fairly extensive period of time (on the order of several months) after the injury was inflicted.

Much confusion had been caused by a small loose sliver of bone within the upper cranial cavity, which was discovered from the same X-ray analysis. Some people have mistaken this visible bone fragment for the supposed head injury. In fact, since Tutankhamun's brain was removed post mortem in the mummification process, and considerable quantities of now-hardened resin introduced into the skull on at least two separate occasions after that, had the fragment resulted from a pre-mortem injury, it almost certainly would not still be loose in the cranial cavity. It therefore almost certainly represented post-mummification damage.

2005 research and findings[]

On March 8, 2005, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass revealed the results of a CT scan performed on the pharaoh's mummy. The scan uncovered no evidence for a blow to the back of the head as well as no evidence suggesting foul play. There was a hole in the head, but it appeared to have been drilled, presumably by embalmers. A fracture to Tutankhamun's left thighbone was interpreted as evidence that suggests the pharaoh badly broke his leg before he died, and his leg became infected; however, members of the Egyptian-led research team recognized, as a less likely possibility, that the fracture was caused by the embalmers. 1,700 images were produced of Tutankhamun's mummy during the 15-minute CT scan.

The research also showed that the pharaoh had cleft palate.[8]

Much was learned about the young king's life. His age at death was estimated at 19 years, based on physical

developments that set upper and lower limits to his age. The king had been in general good health, and there were no signs of any major infectious disease or malnutrition during childhood. He was slight of build, and was roughly 170 cm (5'7") tall. He had large front incisor teeth and the overbite characteristic of the rest of the Thutmosid line of kings to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, though it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathologic in cause. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten (possibly his father, certainly a relation), often featured an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality more typical of a condition like Marfan's syndrome, as had been suggested. A slight bend to his spine was also found, but the scientists agreed that there was no associated evidence to suggest that it was pathological in nature, and that it was much more likely to have been caused during the embalming process. This ended speculation based on the previous X-rays that Tutanhkamun had suffered from scoliosis.

The 2005 conclusion by a team of Egyptian scientists, based on the CT scan findings, confirmed that Tutankhamun died of a swift attack of gangrene after breaking his leg. After consultations with Italian and Swiss experts, the Egyptian scientists found that the fracture in Tutankhamun's left leg most likely occurred only days before his death, which had then become gangrenous and led directly to his death. The fracture was not sustained during the mummification process or as a result of some damage to the mummy as claimed by Howard Carter. The Egyptian scientists have also found no evidence that he had been struck in the head and no other indication he was killed, as had been previously speculated.

Despite the relatively poor condition of the mummy, the Egyptian team found evidence that great care had been given to the body of Tutankhamun during the embalming process. They found five distinct embalming materials, which were applied to the body at various stages of the mummification process. This counters previous assertions that the king’s body had been prepared carelessly and in a hurry.

Discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb[]

Tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and he remained virtually unknown until the early 20th century. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the burial itself. Subsequently, the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some workers huts were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the 20th dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of King Tut was overlooked, presumably because it has been lost and even his name may have been forgotten.

In 1907, just before his discovery of the tomb of Horemheb, Theodore M. Davis's team uncovered a small site containing funerary artifacts with Tutankhamun's name. Assuming that the site was Tutankhamun's complete tomb, Davis concluded the dig. The details of both findings are documented in Davis's 1912 publication, The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou; the book closes with the comment, "I fear that the Valley of the Kings is now exhausted." But Davis was to be proven spectacularly wrong.

The British Egyptologist Howard Carter (employed by Lord Carnarvon) discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (since designated KV62) in Valley of the Kings on November 4, 1922 near the entrance to the tomb of Ramesses VI, thereby setting off a renewed interest in all things Egyptian in the modern world. Carter contacted his patron, and on November 26 that year both men became the first people to enter Tutankhamun's tomb in over 3000 years. After many weeks of careful excavation, on February 16, 1923 Carter opened the inner chamber and first saw the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun.

For many years, rumors of a "curse" (probably fueled by newspapers at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had first entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicates no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not. Indeed, most lived past 70.

Ancient Egyptian senet games were found in the tomb.[9]

Tutankhamun Bust on Lotus

Some of the treasures in Tutankhamun's tomb are noted for their apparent departure from traditional depictions of the boy king. Certain cartouches where the king's name should appear have been altered, as if to usurp the property of a previous pharaoh. However, this may simply be the product of "updating" the artifacts to reflect the shift from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun. Other differences are less easy to dispense, such as the older, more angular facial features of the middle coffin and canopic coffinettes. The most widely accepted theory for these latter variations is that the items were originally intended for Smenkhkare, who may or may not be the mysterious KV55 mummy. Said mummy, according to craniological examinations, bears a striking first-order (father-to-son, brother-to-brother) relationship to Tutankhamun's.[citation needed]

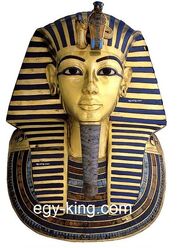

Tutankhamun's Mask[]

It was placed directly on the head of the mummy of Tutankhamun , together with other decorations or trappings such as a golden vertical line of inscriptions and 4 horizontal ones and the golden figure of the Ba bird which was placed on the chest of the mummy, with a big scarab amulet (the heart amulet) inscribed on the other side with Chapter 30B of the Book of the Dead in order to protect the heart of the deceased.

Tutankhamun Mask

The mask itself is made out of pure gold about 10.23 kg representing the facial features of the king. Tutankhamun is wearing the Nemes headdress, which is striped blue and gold as a sign of association with god Ra (Re’s body was believed to be made out of gold and his hair out of lapis lazuli).

The king is represented with a broad collar (wsekh) inlaid with semi-precious stone like Lapis Lazuli (dark blue) and Carnelian (red), Turquoise (light blue) and on either sides of the broad collar there is a representation of the falcon god (Horus).

Tutankhamun in popular culture[]

Tutankhamun is the world's best known pharaoh, partly because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. He has also entered popular culture - he has, for example, been commemorated in the whimsical song "King Tut" by the American comedian Steve Martin. He is the focus of the light hearted song "Dead Egyptian Blues" by the band Trout Fishing in America from their "Over the Limit" album. He was also the namesake of one of Batman's arch enemies in the 1960s American television series "Batman" with Adam West. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his forward to the 1977 edition of Carter's The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, "The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's kings has become in death the most renowned."

Perhaps we will never know what exactly happened to him in a cold winter day in year 1325 BC (based on the types of flowers found in his tomb, it can be assumed that he was interred on March/April, so he would have died between 70-90 days before that, as that much time is required for mummification and other related funeral processes). The most likely reason could be the injuries from a chariot accident.

The major contribution of the boy king could easily be his hastily-prepared tomb, resulting from his untimely death. The spectacular discovery, the sheer size of wealth uncovered, the beautiful artifacts that depicted the love and affection between the ill-fated young royal couple and the flowers placed on the golden mask of the mummy—about which Carter wrote that he would like to imagine them as placed by Ankhesenamun just before the closing of the casket—the list can be endless. All these fueled the imagination of the global public and raised interest in ancient Egypt and its culture to an unprecedented level throughout the world.

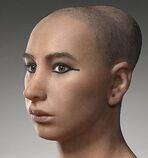

Tutankhamun's appearance and controversy[]

In 2005, three teams of scientists (Egyptian, French and American), in partnership with the National Geographic Society, developed a new facial likeness of Tutankhamun. The Egyptian team worked from 1,700 three-dimensional CT scans of the pharaoh's skull. The French and American teams worked plastic molds created from these – but the Americans were never told whom they were reconstructing.[10] All three teams created silicon busts of their interpretation of what the young monarch looked like.

Skin tone[]

Though modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy based on CT data from his mummy, correctly determining his skin tone is impossible. The problem is not a lack of skill on the part of Ancient Egyptians. Egyptian artisans distinguished accurately among different ethnicities, but sometimes depicted their subjects in totally unreal colors, the purposes for which aren't completely understood. Thus no absolute consensus on King Tut's skin tone is possible.

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to some protestors of the King Tut reconstruction:

- The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We'll never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100 percent certainty. ... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion.[11]

References[]

- ↑ Allen 2006, p. 7, 12-14.

- ↑ Eaton-Krauss 2015, p. 28–29.

- ↑ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 89.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hawass et al. 2010, p. 642–645.

- ↑ Hawass & Saleem 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Tallet 1996.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 29.

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian. "King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show", National Geographic News, March 8, 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Welcome to Senet. Texas Humanities Resource Center (December 17, 2004).

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian. "King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction", National Geographic News, May 11, 2005.

- ↑ Henerson, Evan. "King Tut's skin color a topic of controversy", U-Daily News - L.A. Life, June 15, 2005.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1251731/King-Tutankhamuns-incestous-family- revealed.html

retrieved 4-13-2020 published by dailymail.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/2/100216-king-tut-malaria-bones-inbred-tutankhamun/

retrieved 4-13-2020 pubilshed in 2010 by national geographic.

https://www.jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/185393

Ancestry and Pathology of Tutankhamun's family by dr Zahi Hawass Feb 17 2010

https://www.egy-king.com/2020/08/tutankhamun-meaning.html

Tutankhamun Meaning published by Egy king

retrieved 4-18-2020

Bibliography[]

- Allen, J.P., 2006: Amarna Succession. In: Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane. University of Memphis.

- Eaton-Krauss, M., 2015: The Unknown Tutankhamun. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hawass, Z./Gad, Y.Z./Somaia, I./Khairat, R./Fathalla, D./Hasan, N./Ahmed, A./Elleithy, H./Ball, M./Gaballah, F./Wasef, S./Fateen, M./Amer, H./Gostner, P./Selim, A./Zink, A./Pusch, C.M., 2010: Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family. Journal of the American Medical Association. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association. 303 (7), p. 638–647.

- Hawass, Z./Saleem, S.N., 2016: Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. The American University in Cairo Press.

- Reeves, C.N., 1990: The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames & Hudson, London.

- Tallet, P., 1996: Une jarre de l'an 31 et une jarre de l'an 10 dans la cave de Toutânkhamon. Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, p. 369-383.

- Howard Carter, Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. Courier Dover Publications, June 1, 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discover and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- T. G. H. James, Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, September 1, 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamen: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Thomas Hoving, The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, October 15, 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story. Putnam Adult, April 13, 1998, ISBN 0-425-16689-9 (paperback)/ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding)

- Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0-345-27349-4 (paperback)/ISBN 0-670-72723-7 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Michael Haag, "The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty". London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- John Andritsos, Social Studies of ancient egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006

External links[]

- End Paper: A New Take on Tut's Parents by Dennis Forbes (KMT 8:3 . FALL 1997, KMT Communications)

- The mummy's curse: historical cohort study (Mark R Nelson, British Medical Journal 2002;325:1482

- Tutankhamun tomb treasures by Egy king

| Predecessor: Smenkhkare |

Pharaoh of Egypt Eighteenth Dynasty |

Successor: Ay |