| Preceded by: Nemtyemsaf I |

Pharaoh of Egypt 6th Dynasty |

Succeeded by: Nemtyemsaf II | |

| Pepi II | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reign | c. 2278-2184 BC (94 years) | ||

| Praenomen | Neferkare Perfect Soul of Re | ||

| Nomen | Pepi | ||

| Horus name | Netjerkhau Divine of Apparitions | ||

| Nebty name | Netjerkhau Divine of Apparitions | ||

| Golden Horus | Sekhembiknub The Powerful Golden Falcon | ||

| Father | Nemtyemsaf I or Pepi I | ||

| Mother | Ankhesenpepi II | ||

| Consort(s) | Neith, Iput II, Ankhesenpepi III, Ankhesenpepi IV | ||

| Burial | Pyramid of Pepi II at Saqqara | ||

- For other pages by this name, see Pepi.

Neferkare Pepi II (c. 2284 BCE - c. 2184 BCE) was a ruler of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom. His throne name, Neferkare (Nefer-ka-Re), means "Beautiful is the Ka of Re". He was once thought to be the son of Pepi I and Queen Ankhesenpepy II but it is now believed Pepi II was rather the son of Merenre, who married Ankhesenpepy after Pepi I's death--based on an inscription from a block of white limestone from her mortuary temple, according Audran Labrousse, director of the French Archaeological Mission.[1] Pepi II would, hence, be the grandson of Pepi I instead. He succeeded to the throne at age six, after the premature death of his father, and is generally thought to have ruled for 94 years (c. 2278 BC - c. 2184 BC), the longest reign of any monarch in history, though this has been disputed by some Egyptologists who favour a shorter reign length of 64 years, given the absence of attested dates known for Pepi after his 31st Count. (Year 62 if biennial) His reign marked a sharp decline of the Old Kingdom. While the power of the nomarchs grew, the power of pharaoh dissolved. With no dominant central power, local nobles began raiding each other's territories.

1337 1337[]

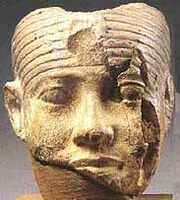

Ankhnesmeryre II and Pepi II

His mother Ankhsenpepy II most likely ruled as regent in the early years of his reign. An alabaster statuette in the Brooklyn Museum depicts a young Pepi II, in full kingly regalia, sitting on the lap of his mother. Despite his long reign, this piece is one of only three 3D representations (i.e. statuary) in existence of this particular king. She may have been helped in turn by her brother Djau, who was a vizier under the previous king. Some scholars have taken the relative paucity of royal statuary to suggest that the royal court was losing the ability to retain skilled artisans.

A glimpse of the personality of the early child king can be found in a letter he wrote to Harkhuf, a governor of Aswan and the head of one of the expeditions he sent into Nubia. Sent to trade and collect ivory, ebony and other precious items, he captured a pygmy. News of this reached the royal court, and an excited young king sent word back to Harkhuf that he would be greatly rewarded if the pygmy were brought back alive, likely to serve as an entertainer for the court. This letter was preserved as a lengthy inscription on Harkhuf's tomb, and has been called the first travelogue.[1][2]

Wives[]

Over his long life Pepi II had several wives, thought to include Neith (A), Iput II, Ankhenespepy III, Ankhenespepy IV, and Udjebten. Following a long tradition of royal incestuous marriage, Neith she was the mother of Pepi's successor Merenre Nemtyemsaf II, She could be a daughter of Ankhesenpepi I and hence also Pepi II's cousin and maybe half sister and Iput was his niece (a daughter of his father Merenre). Of these queens, Neith, Iput, and Udjebten each had their own minor pyramids and mortuary templates as part of the king's own pyramid complex in Saqqara.

Foreign Relations[]

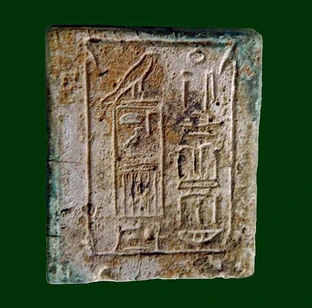

A plate mentioning Pepi II's first heb sed jubilee.

It is thought that Pepi II carried on in the tradition of his predecessors and continued with existing foreign relations, and possibly expanding further trade links into southern Africa. Copper and turquoise mining were undertaken at Wadi Maghara, and alabaster was quarried from Hatnub, both in the Sinai. There is at least one trade expedition to Punt recorded. Diplomatic records also exist of missions to Byblos in ancient Palestine.

Pepi II is thought to have taken a policy of pacification in Nubia, with Harkhuf making at least two further expeditions into the area. Over time it appears as though relations grew strained, for while Harkhuf managed to return safely from each of his expeditions, one of his successors was not so lucky.

There were also military forays into adjacent lands, but it is noted that there was an increasing reliance upon Libyan and Nubian mercenaries. Further possible evidence of a relative lack of success in these ventures comes from the fact that a scene from the king's pyramid, depicting him as a Sphinx trampling his enemies — including a Libyan chieftain and his family — is wholly derivative from the mortuary complex of previous pharaoh Sahure, which calls into question the veracity of the events supposedly being depicted.

It is also known that near the end of his reign, some foreign relations were completely broken off, a further sign of the disintegration of central rule.

The Decline of the Old Kingdom[]

The decline of the Old Kingdom arguably began before the time of Pepi II, with nomarchs (regional representatives of the king) becoming more and more powerful and exerting greater influence. Pepi I for example, married two sisters who were the daughters of a nomarch and later made their brother a vizier. Their influence was extensive, both sisters bearing sons who were chosen as part of the royal succession: Merenre and Pepi II.

Increasing wealth and power appears to have been handed over to high officials during Pepi II's reign. Large and expensive tombs appear at many of the major nomes of Egypt, building by the reigning nomarchs, the priestly class and other administrators. Nomarchs were traditionally free from taxation and their positions became hereditary. Their increasing wealth and independence led to a corresponding shift in power away from the central royal court to the regional nomarchs.

Later in his reign it is known that Pepi divided the role of vizier into two: one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower, a further decentralization of power away from the royal capital of Memphis. Further, the seat of vizier of Upper Egypt was moved several times. The southern vizier was stationed at Thebes.

It is also thought that Pepi II's extraordinarily long reign may have been a contributing factor to the general breakdown of centralized royal rule. While there are some doubts that he reigned as long as 94 years (some scholars such as Von Beckerath believe this to be a misreading of long-lost original texts by early historians such as Manetho, and ascribe him a seemingly more realistic figure of 64 years, which seems more feasible if he was succeeded by his son as Egyptian tradition states, rather than a grandson. Still all scholars concede that his reign was unusually long. This situation almost certainly produced a succession crisis and also led to a stagnation of the central administration. A better documented example of this type of problem can be found in the long reign of much later Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II and his successors. It should be stressed that Pepi II's highest date is the "Year after the 31st Count, 1st Month of Shemu, day 20" from Hatnub graffito No.7, according to Spalinger.[2] This date would be equivalent to only Pepi II's Year 62 (on the biennial dating system) and conforms well with the suggestion of a 64 Year reign for him by Von Beckerath given the noticeable absence of known dates for Pepi II from his 33rd to 47th Count. A previous suggestion by Hans Goedicke that the Year of the 33rd Count appears for Pepi II in a royal decree for the mortuary cult of Queen Udjebten was withdrawn by Goedicke in 1988 in favour of a reading of 'the Year of the 24th Count' instead, notes Spalinger.[3]

Pyramid Complex[]

Pepi II's pyramid complex (originally known as Pepi's Life is Enduring) is located in Saqqara, close to many other Old

Pepi II's pyramid complex

Kingdom pharaohs. His pyramid is a modest affair compared to the great pyramid builders of the Fourth Dynasty, but was comparable to earlier pharaohs from his own dynasty. It was originally 78.5 metres high, but erosion and relatively poor construction has reduced it 52 metres.

The pyramid was the center of a sizable funerary complex, complete with a separate mortuary complex, a small, eastern satellite pyramid. This was flanked by two of his wives' pyramids to the north and north-west (Neith (A) and Iput II respectively), and one to the south-east (Udjebten), each with their own mortuary complexes. Perhaps reflecting the decline at the end of his rule, the fourth wife, Ankhenespepy IV was not given her own pyramid but was instead buried in a store room of the Iput's mortuary chapel. Similarly, Prince Ptahshepses, who likely died near the end of Pepi II's reign, was buried in the funerary complex of a previous pharaoh, Unas, within a "recycled" sarcophagus dating to the Fourth Dynasty.

The ceiling of the burial chamber is decorated with stars, and the walls are lined with passages from the Pyramid texts. An empty black sarcophagus bearing the names and titles of Pepi II was discovered inside.

Following in the tradition of the final pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty, Unas and of his more immediate predecessors Teti, Pepi I and Merenre, the interior of Pepi II's pyramid is decorated with what has become known as the pyramid texts, magical spells designed to protect the dead. Well over 800 individual texts (known as "utterances") are known to exist, and Pepi II's contains 675 such utterances, the most in any one place.

It is thought that this pyramid complex was completed no later than the thirtieth year of Pepi II's reign. No notable funerary constructions of note happened again for at least 30, and possibly as long as 60 years, due indirectly to the king's incredibly long reign. This meant there was a significant generational break for the trained stonecutters, masons, and engineers who had no major state project to work on and to pass along their practical skills. This may help explain why no major pyramid projects were undertaken by the subsequent regional kings of Herakleopolis during the First Intermediate Period.

Excavation[]

The complex was first investigated by John Shae Perring, but it was Gaston Maspero who entered it first in 1881. Gustav Jequier investigated in detail between 1926 and 1932.

Portraiture[]

Only two statues identified as representing Pepi II exist. This is despite the fact that he was the longest reigning monarch of Ancient Egypt. Even more curious, both of these portraits depict Pepi II as a young child. The first of these, in the Brooklyn Museum, has Queen Ankhenesmerire balancing the baby Pepi II on her knee. The second, a small statue in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo shows Pepi II as a naked child, squatting on the child with his legs apart with his right hand (now missing) touching his mouth (a symbolic gesture of childhood for the god Horus). No other statues of Pepi II are known, though portraits of him as a grown man appear as relief carvings on his funerary complex.

Successors[]

There are few official contemporary records or inscriptions of Pepi's immediate successors, and for this reason in many books Pepi II is typically credited as being the last verifiable pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty and of the Old Kingdom.

However, according the Manetho and the Turin King List, he was succeeded by his son Merenre II, who reigned for just over a year. He in turn may have been succeeded by Nitocris, who was likely Merenre II's sister as well as wife. If she did in fact rule, she would be the first female ruler of Egypt. According to the story as told by Manetho, Merenre II was assassinated, and Nitocris saw to it that his murderers were punished prior to committing suicide. There is now considerable doubt in the academic community as to whether she in fact existed, given the paucity of physical evidence in such things as the various Kings Lists attesting to her rule.

This was the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, a prelude to the roughly 200-year span of Egyptian history known as the First Intermediate Period.

References[]

| Predecessor: Nemtyemsaf I |

Pharaoh of Egypt Sixth Dynasty |

Successor: Nemtyemsaf II |